Integrating Alternative Medicine into National Healthcare Systems in Nigeria and Africa: Prospects, Pitfalls, and Policy Imperatives by Livy‑Elcon Emereonye.

Integrating Alternative Medicine into National Healthcare Systems in Nigeria and Africa: Prospects, Pitfalls, and Policy Imperatives by Livy‑Elcon Emereonye

Abstract. The integration of alternative and traditional medicine into national healthcare systems has emerged as a critical global health policy issue. With the World Health Organization (WHO) estimating that up to 80% of the population in some regions rely on traditional medicine for primary healthcare, the dichotomy between orthodox biomedicine and alternative medical systems is increasingly untenable. This article critically examines the scientific, clinical, economic, and regulatory implications of integrating alternative medicine into national healthcare frameworks. Drawing on peer‑reviewed literature, WHO policy documents, and case studies from Asia, Africa, and Europe, the paper analyzes the potential benefits—such as improved access, cultural acceptability, preventive care, and economic development—alongside significant challenges, including safety concerns, evidence gaps, professional conflict, and regulatory complexity. The article argues that integration is neither an ideological concession nor a cultural indulgence, but a scientifically negotiable and policy‑driven process that must be anchored in evidence‑based evaluation, robust regulation, and ethical governance.

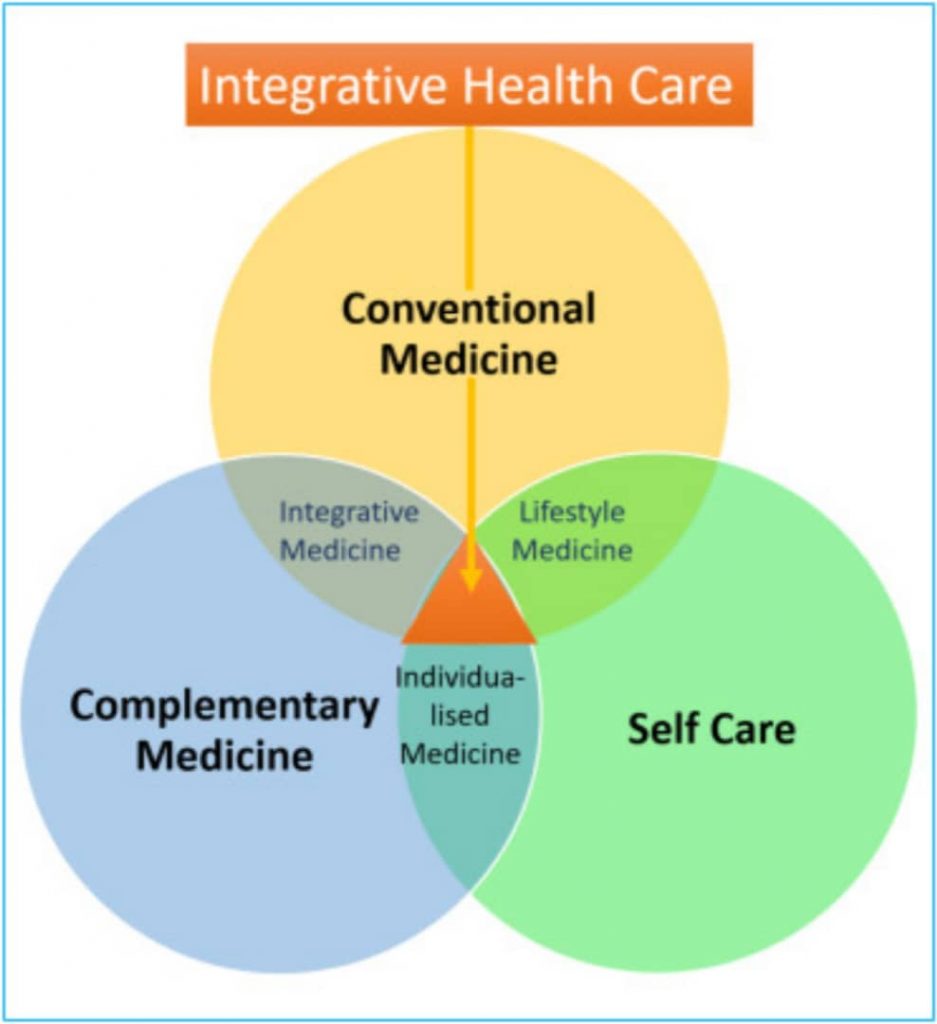

Introduction. Healthcare systems across the world are under unprecedented strain. In Nigeria and much of sub‑Saharan Africa, this strain is intensified by underfunding, workforce shortages, high out‑of‑pocket expenditure, and uneven distribution of healthcare infrastructure between urban and rural areas (Federal Ministry of Health [FMoH], 2016). Rising burdens of chronic non‑communicable diseases, escalating healthcare costs, workforce shortages, and inequitable access to care have forced governments to reconsider long‑standing assumptions about health service delivery. Within this context, alternative medicine—often used interchangeably with traditional, complementary, or integrative medicine—has re‑entered mainstream policy discourse (WHO, 2019). Alternative medicine encompasses a wide range of practices, including herbal medicine, traditional African medicine, Ayurveda, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), homeopathy, naturopathy, and mind–body interventions. While these systems differ in philosophy and practice, they share a common marginalization within dominant biomedical paradigms. Yet paradoxically, they remain widely utilized by populations who perceive them as accessible, culturally resonant, and effective, particularly for chronic and preventive care (Bodeker & Kronenberg, 2002). The central policy question is no longer whether alternative medicine exists within national health landscapes—it clearly does—but whether its integration into formal healthcare systems can be achieved safely, scientifically, and ethically. This article provides a comprehensive scientific analysis of the pros and cons of such integration, with particular attention to regulatory science, clinical evidence, and health systems governance. Conceptual and Scientific Basis for Integration. Integration of alternative medicine into national healthcare does not imply the uncritical acceptance of all traditional practices. Rather, it denotes a structured process whereby validated alternative therapies are incorporated into healthcare delivery, education, research, and regulation alongside conventional medicine (Maizes et al., 2009). From a systems science perspective, health outcomes are shaped by biological, psychological, social, and environmental determinants. Biomedicine, while highly effective in acute and technologically intensive care, often addresses disease at a reductionist level. Many alternative medical systems adopt a holistic framework that emphasizes balance, lifestyle modification, and long‑term prevention. Integrative healthcare models seek to combine these strengths rather than position them as mutually exclusive (Jonas & Rosenbaum, 2011). Pros of Integrating Alternative Medicine into National Healthcare in Nigeria and Africa Improved Access and Equity In Nigeria and many African countries, alternative medicine practitioners are frequently the first—and sometimes the only—point of contact for healthcare, especially in rural and peri‑urban communities. Geographic proximity, affordability, and sociocultural trust make traditional medicine indispensable in underserved communities (WHO, 2013). Formal integration can enhance referral systems, improve surveillance, and reduce delays in accessing higher‑level care. Economic and Developmental Benefits The integration of alternative medicine has significant economic implications. Herbal medicine development, for example, stimulates local agriculture, conservation of medicinal plants, and pharmaceutical innovation. Countries such as China and India have demonstrated that state‑supported integration can generate substantial economic returns through exports, medical tourism, and domestic industry growth (Patwardhan et al., 2015). For African countries, integration presents an opportunity to transition from raw material exportation to value‑added phytopharmaceutical production. When aligned with good manufacturing practices (GMP) and pharmacovigilance systems, this sector can contribute meaningfully to national development. Preventive and Chronic Disease Management. Non‑communicable diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and arthritis require long‑term management strategies that extend beyond pharmacotherapy. Evidence suggests that certain alternative medicine interventions—such as lifestyle‑focused naturopathy, herbal adjuncts, and mind–body therapies—can improve quality of life, adherence, and patient satisfaction (Ernst, 2011). Integrative models have shown promise in oncology supportive care, pain management, and mental health, where complementary therapies reduce symptom burden and enhance overall wellbeing (National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health [NCCIH], 2022). Cultural Legitimacy and Patient‑Centered CareHealthcare systems that disregard cultural beliefs risk alienating patients and undermining adherence. Integration acknowledges indigenous knowledge systems and fosters trust between providers and communities. This cultural legitimacy can enhance public health messaging, vaccination uptake, and chronic disease education when traditional practitioners are engaged as stakeholders rather than adversaries (Hollenberg & Muzzin, 2010). Cons and Challenges of Integration in the Nigerian and African Context Safety and Quality Concerns. One of the most significant challenges is ensuring safety and quality control. Herbal medicines are susceptible to contamination with heavy metals, pesticides, or adulterants, and variability in plant species and preparation methods complicates standardization (Ekor, 2014). Without rigorous pharmacovigilance, integration risks exposing populations to avoidable harm.Evidence Gaps and Methodological ChallengesWhile some alternative therapies are supported by randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews, many lack high‑quality evidence. Conventional biomedical research methods are not always well‑suited to individualized or multi‑component interventions typical of traditional medicine systems (Patwardhan & Mashelkar, 2009). This evidence gap fuels skepticism among orthodox professionals and raises legitimate concerns about cost‑effectiveness and clinical efficacy. Integration therefore demands sustained investment in adaptive research methodologies, including pragmatic trials and real‑world evidence studies.Regulatory and Policy Complexity Integrating alternative medicine requires comprehensive regulatory frameworks covering practitioner licensing, product approval, education standards, and ethical practice. Weak regulation can legitimize quackery, while overly restrictive policies may suppress valuable practices. Achieving regulatory balance is particularly challenging in pluralistic health systems with limited institutional capacity (WHO, 2019). Professional Resistance and Interdisciplinary Conflict Integration often disrupts entrenched professional hierarchies. Physicians and pharmacists may perceive alternative practitioners as threats to professional authority, while traditional healers may resist biomedical oversight. Without clear scopes of practice and collaborative models, integration can degenerate into conflict rather than synergy (Baer, 2008). Risk of Commercial ExploitationThe formalization of alternative medicine increases the risk of biopiracy and unethical commercialization. Indigenous knowledge may be patented without equitable benefit‑sharing, undermining community trust and cultural heritage. Ethical integration must therefore incorporate intellectual property protections and community consent mechanisms (Posey & Dutfield, 1996). Policy and Scientific Pathways for Responsible Integration in Nigeria and AfricaSuccessful integration in Nigeria and Africa requires a multi‑layered approach grounded in science, governance, and existing regulatory institutions such as the Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH), the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), and traditional medicine boards at state levels. Key strategies include: 1. Establishing national integrative medicine policies aligned with WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy. 2. Investing in interdisciplinary research institutes focused on medicinal plants and integrative care. 3. Implementing robust regulatory systems for products and practitioners. 4. Incorporating evidence‑based alternative medicine into medical and pharmacy curricula. 5. Strengthening pharmacovigilance and adverse event reporting systems.Countries that have pursued these pathways—including Nigeria through its National Policy on Traditional Medicine and Ghana via its Traditional Medicine Practice Act—demonstrate that integration is feasible when guided by political will and scientific discipline.In conclusion the Nigerian and African ImperativeIntegrating alternative medicine into national healthcare systems is a complex but unavoidable policy frontier. The potential benefits—expanded access, economic development, preventive care, and cultural legitimacy—are substantial, but so are the risks if integration is pursued without evidence, regulation, and ethical clarity. The debate should not be framed as tradition versus science, but as how science can engage tradition without erasing it. Ultimately, integration in Nigeria and Africa is a test of institutional maturity and regulatory courage. Health systems capable of rigorous evaluation, respectful collaboration, and patient‑centered governance will harness the strengths of both paradigms. Those that succumb to ideological rigidity—whether biomedical or traditional—risk perpetuating inequity and inefficiency in an already strained global health landscape.ReferencesBaer, H. A. (2008). Toward an integrative medicine: Merging alternative therapies with biomedicine. Rowman & Littlefield.Bodeker, G., & Kronenberg, F. (2002). A public health agenda for traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine. American Journal of Public Health, 92(10), 1582–1591. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.92.10.1582Ekor, M. (2014). The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 4, 177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2013.00177Ernst, E. (2011). Complementary and alternative medicine: What is it all about? British Medical Journal, 322(7278), 1133–1135.Hollenberg, D., & Muzzin, L. (2010). Epistemological challenges to integrative medicine: An anti‑colonial perspective on the combination of complementary/alternative medicine with biomedicine. Health Sociology Review, 19(1), 34–56. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2010.19.1.34Jonas, W. B., & Rosenbaum, E. (2011). The integrative medicine solution. Rodale.Maizes, V., Rakel, D., & Niemiec, C. (2009).

Integrative medicine and patient‑centered care. Explore, 5(5), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2009.06.008 National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (2022). Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: What’s in a name? https://www.nccih.nih.govPatwardhan, B., & Mashelkar, R. A. (2009). Traditional medicine-inspired approaches to drug discovery: Can Ayurveda show the way forward? Drug Discovery Today, 14(15–16), 804–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2009.05.009Patwardhan, B., Mutalik, G., & Tillu, G. (2015). Integrative approaches for health: Biomedical research, Ayurveda and Yoga. Academic Press.Posey, D. A., & Dutfield, G. (1996). Beyond intellectual property: Toward traditional resource rights for indigenous peoples and local communities. IDRC.World Health Organization. (2013). WHO traditional medicine strategy 2014–2023. WHO Press.World Health Organization. (2019). WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019. WHO Press.Federal Ministry of Health. (2016). National policy on traditional medicine. Abuja: FMoH.National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control. (2021). Guidelines for registration of herbal medicinal products in Nigeria. Abuja: NAFDAC.

Livy-Elcon Emereonye Writes from Lagos Nigeria